Election 2016 is underway and it’s clear something is stirring. Political outsiders are making waves, while more polished pols are sinking.

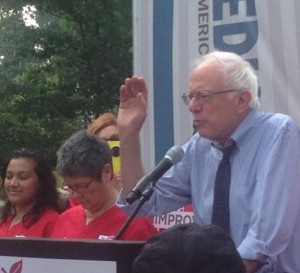

The top two candidates on the Republican side, Donald Trump and Ben Carson, have never held elected office. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders, a 74-year-old socialist senator from Vermont, is drawing mass crowds and fast becoming the front-runner. Meanwhile in Britain, Jeremy Corbyn, a self-described democratic socialist, shocked odds makers, who pegged his chances of becoming Labour leader at 200 to 1.

On both sides of the Atlantic and both sides of the aisle people are expressing their dissatisfaction. While observers are quick to compare Sanders to Corbyn, there’s a key difference: foreign policy. Corbyn has for years been unapologetic in his critique of U.K. and U.S. foreign policy and their shared emphasis on “regime change,” which has destabilized the Middle East and led to the creation of ISIS.

Sanders, meanwhile, is more muted. Under “Issues,” Sanders’ campaign website has a tab for the Iran Deal (which he supports), but not one laying out his broader foreign policy – which led to a petition signed by more than 26,000 calling on him to address the “crucial issues of war, militarism and foreign policy.” While Sanders is quick to highlight his vote against the Iraq War, that was 13 years ago.

Sanders’ chief opponent for the Democratic nomination, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, is more hawkish. She voted for the Iraq War as senator, and as secretary pushed for U.S. intervention in Libya to overthrow Gaddafi, which wrecked the country.

The last major party presidential candidate to seriously question the policy of “regime change” was Ron Paul. Despite being a little-known congressman from Texas, Paul punched above his weight in two attempts to secure the Republican nomination. In 2012, Paul stood out at the debates when he proposed dialoguing with Iran. In primaries across the country Paul’s anti-war message won over large numbers of voters – Republican voters.

In a recent interview about the Iran deal, which he called “to the benefit of world peace,” Paul said, “We have learned and been conditioned to distrust and hate the Persians, and that they’re gonna kill us… But there’s no history to show that Iran[ians] are aggressive people. When’s the last time they invaded a country? Over 200 years ago!”

This election cycle Ron Paul’s son, Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, offers similar positions on foreign policy, but he’s wavered. After saying, “ISIS exists and grew stronger because of the hawks in our party who gave arms indiscriminately,” he backed away from his statement. Sen. Paul also joined with 46 fellow Republican senators in signing a letter to Iranian leaders in an attempt to undermine the Iran Deal, which his father supports.

While there may be a grassroots desire among voters in both parties to end the U.S. policy of “regime change,” that’s not reflected in their candidates, leaving a lot of room for an outsider.

In response to the Syrian refugee crisis, the Green Party released a statement which called on the U.S. to take in a number of refugees “commensurate with the U.S. role in having created the crisis.” In addition to expanded aid, the party called for “an end to interventionist ‘regime change’ policies that continue to provoke violent conflict and displacement of civilians.”

“The present crisis of refugees from Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria is the inevitable consequence of a foreign policy that puts oil profits, weapons sales and support for totalitarian regimes above people, planet, and peace,” Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein wrote on Facebook.

While there are structural obstacles preventing minor parties from reaching American voters – including televised presidential debates controlled by the two major parties – the Green Party’s anti-interventionist message may resonate. Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn can attest that it wouldn’t be the first time.