Listen to Lucas Benitez HERE:

Audio clip: Adobe Flash Player (version 9 or above) is required to play this audio clip. Download the latest version here. You also need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser.

Yesterday, millions of Americans enjoyed a Thanksgiving Dinner made possible by some of the most underpaid and overlooked workers in the United States. While food production is increasingly controlled by a handful of the largest corporations on earth, the plentiful choices at grocery stores is made possible by farmworkers, who are too often very poorly paid.

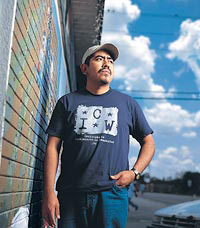

Lucas Benitez, one of the founders of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, was in Washington, D.C. this summer to promote C.I.W.’s traveling Modern Day Slavery Museum. Today, C.I.W. has nearly 5,000 members and regularly forces some of the largest corporations on earth to the negotiating table, but the organization had quite humble beginnings. In 1992, Benitez and seven other farmworkers in Immokalee, Florida began meeting Wednesday evenings at 7:00 PM at a local church to discuss the injustices they faced. Prior to the founding of C.I.W., Immokalee farmworkers did not have an organization they could turn to when growers withheld their wages, or even when they were beaten, Benitez said.

The discreet Wednesday evening meetings brought together individuals from different nationalities – Mexican, Guatemalan, Haitian. C.I.W. encouraged pickers not to be divided, but instead to see themselves as the industry saw them. Benitez said, “We saw that the agricultural industry and the companies that buy those tomatoes see us just as workers. It doesn’t matter to them what country we’re from or if we have a family or not. All that matters is how fast you pick. They look at us as if we were just machines. And so we saw that we also had to look at ourselves just as workers in that same way: That we were all together and unite to change the conditions.”

From this base of solidarity, C.I.W. began regularly demonstrating at the homes of growers who withheld wages. The tactic of embarrassing growers in front of their neighbors was so successful that in the first year alone C.I.W. was able to reclaim $100,000 in back wages, Benitez said. This activism was followed in 1994 and 1995 by two general strikes and an anti-violence strike in 1996 which brought 500 farmworkers to the home of an abusive crew leader, Benitez said.

In 2001, C.I.W. launched its “Campaign for Fair Food” with a boycott of Taco Bell. Four years later, Taco Bell agreed to all of C.I.W.’s demands, including paying farmworkers a penny more per pound of tomatoes picked. C.I.W. explained the need for the Penny Per a Pound increase in wages: “Tomato pickers earn 40-50 cents for every 32-lb bucket of tomatoes they harvest – a rate that has not risen significantly since 1978. A worker must pick nearly 2.5 tons of tomatoes just to earn a minimum wage for a typical 10-hour day. Grinding poverty leaves farmworkers vulnerable to the most exploitative employers, often resulting in egregious labor rights abuses.”

Following their victory over Taco Bell, C.I.W. brought McDonald’s to the negotiating table, winning even further demands than in the Taco Bell campaign. Burger King, Subway, Whole Foods, and other large buyers all followed suit after increasingly shorter campaigns against them.

Presently, C.I.W. is attempting to negotiate with Publix, Kroger, Trader Joe’s and Ahold, the parent company for Stop & Shop and Giant grocery stores. To date, these companies have been reluctant to sit down with C.I.W. to discuss how to end subpoverty wages and abuses faced by the farmworkers who pick their tomatoes. To learn more about the effort to improve the conditions farmworkers face watch this video and visit www.ciw-online.org.